1968 Preservation Hall Portraits by Larry Borenstein, Bill Russell & Noel Rockmore

Preservation Hall, like the paintings which line its walls, started casually and grew in importance. No one anticipated the new interest in New Orleans jazz or the reaction to these paintings. The chain of events is so much the history of my Gallery that I think I should tell it in the first person.

In 1952 I moved my gallery to 726 St. Peter Street. The building had been occupied by a succession of creative people. Its architecture (it was built before 1800 as a Spanish tavern) and its location (next door to Pat O’Brien’s) suited it for the display and sale of paintings. I coined the name “Associated Artists Studio” and worked cooperatively with the available talents. The location demanded night hours which interfered with my listening to jazz. I found that by my closing time most bands had knocked off. Occasionally I got to hear Billie and DeDe at Luthjens or some weekends I crossed the river to hear Kid Thomas at the Moulin Rouge. This was not nearly enough music for me. I bought an old piano and invited the musicians to come to the gallery. I supplied beer and passed a kitty. These sessions (called rehearsals to avoid union trouble) were closed; only people I knew or who seemed interested were invited. If music got under way without prearrangement I phoned friends to pass the word to insure an audience. Sometimes the musicians divided a few dollars; other times (usually when some generous out-of-towner worked his way in) the rewards were better.

An unexpected byproduct of the sessions was a series of jazz watercolors done between 1952 and 1954 by Sidnew Kittinger. They were vivid impressions executed with a freshness which made them popular. To my surprise they sold readily. Soon Andrew Lang, Harold Quistgard, Joan Farrar, Richard Bell and Dick Hoffman felt the urge and a variety of jazz paintings resulted.

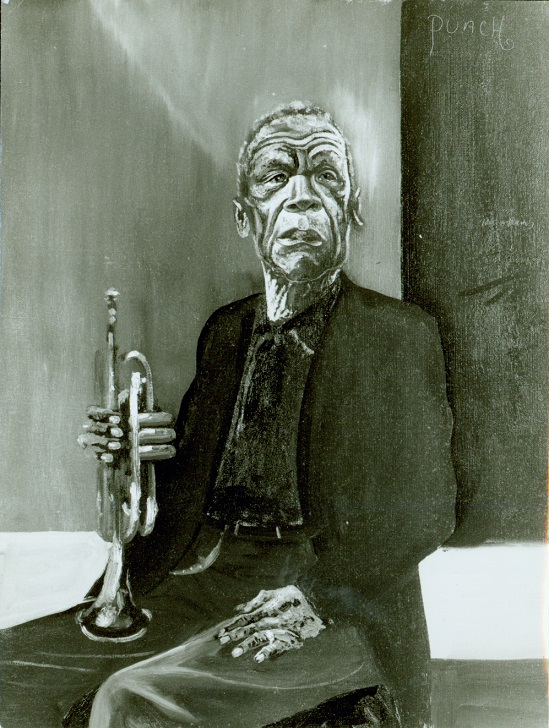

The concerts took place regularly. Punch Miller, back from his long years on the road, brought a band to the Gallery Tuesday nights. Kid Thomas had a “rehearsal” every Thursday night. Sundays Noon Johnson often stopped by with his trio. Piano “professors” Stormy Weatherly, John Smith and Isadore Washington often dropped in as did busking guitarists, banjoists and harmonica virtuosos. Often impromptu sessions got underway just because Lemon Nash dropped in to say “hello” and just happened to have his ukelele with him.

As the interest in the music grew so did resistance. Neighbors who found they could live comfortably with Pat O’Brien’s music found ours something to complain about. The police calls (never enough to really stop the activity) became a constant source of apprehension. On two or three occasions the police sent the paddy wagon and jailed everybody. The bands frequently included white and Negro musicians and it was simpler to charge them with “disturbing the peace” than with breaking down segregation barriers.

These were changing times in New Orleans and the mood was often reflected in night court. A certain judge managed to combine the judicial dignity of a kangaroo court and the philosophy of lynch law with the humor of Milton Berle. An arch-conservative, he was outraged at any racial mixing. When cases of this sort came before him the courtroom was treated to a tirade on white supremacy spiced withe raucous humor and homely philosophy expressed in curbstone epithets. “His Honor” was a mimic and often parodied a defendant. Sometimes he delivered a diatribe if he thought the defendant’s hair was too long. On other occasions he would treat the courtroom to an uninhibited dissertation on social ills and often in the midst of his declamation he would call for order and threaten to clear the courtroom if the laughter which he had provoked was not stilled.

One night in 1957 Kid Thomas and several musicians white and colored stood before him. In stern tones the judge delivered a lecture. “We don’t want Yankees coming to New Orleans mixing cream with our coffee.” He went on to say that Thomas Valentine was well liked by decent folk in Algiers and also appreciated as a “good yard boy”. People thought well of him for giving cornet lessons to West Bank kids and if he would remember his place in the future and not get “uppity” he would let him go this time.

The sessions grew in popularity. I moved my gallery next door and the old building was used exclusively for music. In 1960 Grayson Mills decided to record Punch Miller. He wanted nightly rehearsals with an audience and was surprised to find that the kitty collection enabled him to actually pay the band union scale. This led to an agreement with the musicians union permitting nightly concerts and Preservation Hall came out from underground.

A club was formed with the pretentious title of The Society for the Preservation of Traditional New Orleans Jazz. Alas, as in most jazz clubs, there was as much feuding as music, and the music suffered. I realized that the only hope was to put the activity on a business-like basis. The club was dissolved and Allan and Sandra Jaffee undertook to operate Preservation Hall as a business. They were enthusiastic and willing to take the risks of this unlikely venture. At first it was necessary to subsidize the Hall. They took daytime jobs to help support the nightly concerts. We all hoped that if the music could be presented a paying audience for it would develop. The kitty policy was continued but they found that unless a listener was willing to chip in enough to help pay for the band he should not be admitted.

This in effect established a minimum donation and without this policy Preservation Hall could not have survived. In practice it is handled with great flexibility. Sandy, an excellent judge of character, frequently invites students, foreigners, musicians and other persons whom she deems deserving to come in as guests. On the other hand she is adamant in her insistence that a donation be given by those who impress her as merely satisfying their curiosity. Of course, most people who come to the Hall genuinely like the music and are glad for an opportunity to help support it.

Another decision concerned requests. Overworked favorites such as “The Saints” and “Tiger Rag” were played several times each night and lesser known traditional numbers were rarely heard. The now famous request sign was lettered and hung. It reads: “Traditional Requests $1; Others $2; The Saints $5". To make a request it is necessary that the money go into the kitty. The number of requests diminished and the leader can call his own tunes. Usually the leader of a New Orleans band is aware of his audience and knows when to play a vocal, a fast number or a slow number. This policy change improved the quality of the music.

In 1961 I commissioned Xavier de Callatay to do a series of oils of the musicians. Several were done in a pleasing, skillful manner but they fell short of my expectations as definitive paintings to document the jazzmen. By 1962 I had given up hope that any significant group of paintings would evolve. Just when this goal seemed unattainable Noel Rockmore returned to New Orleans and did a few sketches. These delighted me. He seemed to plumb the very depths of the souls of the musicians - the pathos, the despair, the heroism, the irony.

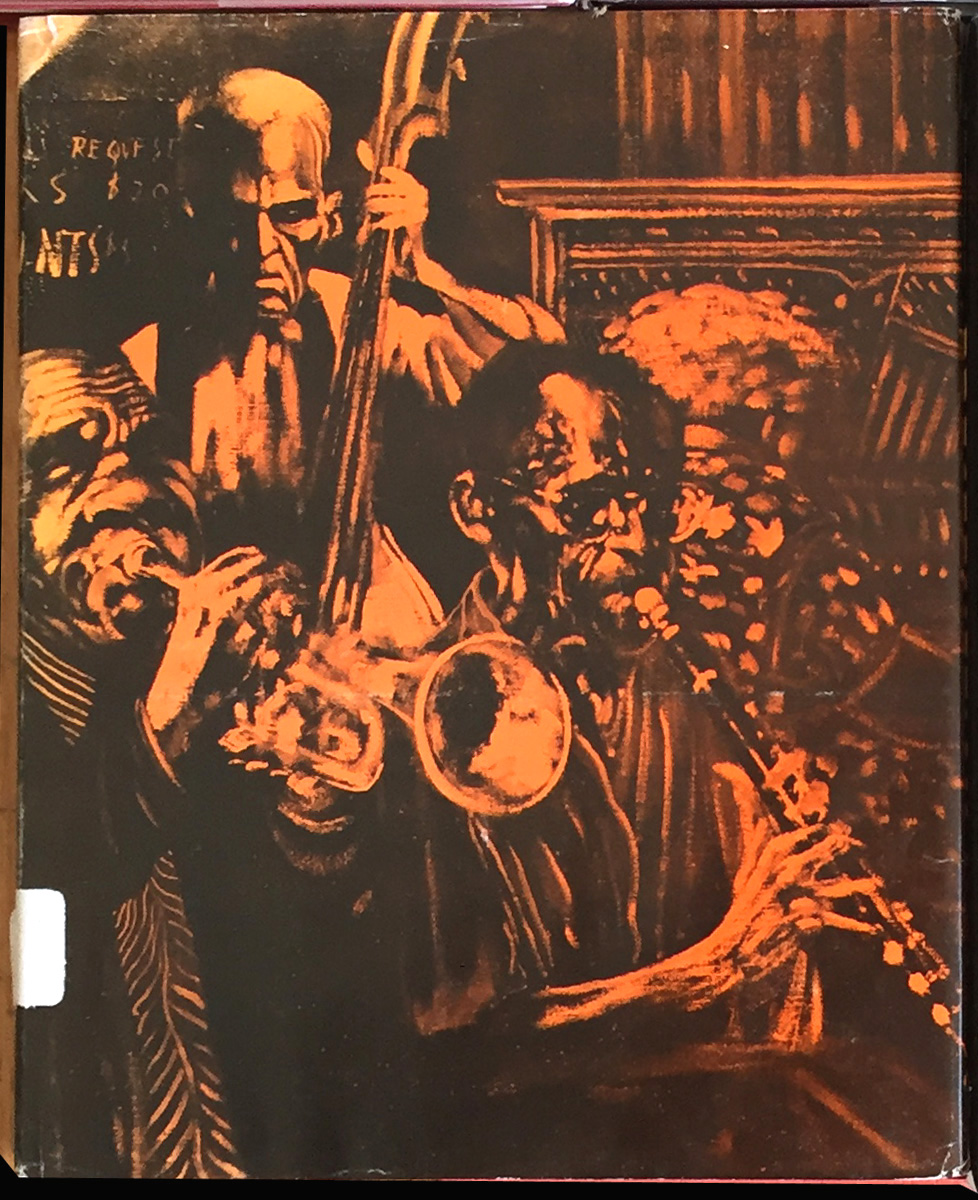

Night after night for months Rockmore took up a vantage point in the Hall and painted furiously. Quickly in the dim light using masonite and polymer he captured what he heard, what he felt and what he saw. Polymer, a relatively new acrylic medium, dries immediately. Most painters shun it because it does not allow time to make painting decisions. For Rockmore this characteristic was an asset. Most of the paintings were accomplished during a thirty-minute set and it was not unusual for three or four to result from a single night’s work. The paintings combined unmistakable likenesses of the musicians, unerring composition and superb technique. They could only spring from an artist’s creative instinct. He selected from the hundreds of sensations that essence which when set down permits the viewer to share his experience. He seemed to relish the distractions and some of the best paintings were produced on the most crowded nights. The audience at Preservation Hall soon learned that Rockmore took his work seriously. Occasionally a well-meaning tourist would peek over his shoulder only to be treated as an unwelcome intruder. At closing time Noel gathered up the work and we discussed each piece. Occasionally we agreed that one should be destroyed but most of the paintings contained the mystic spirit of Art.

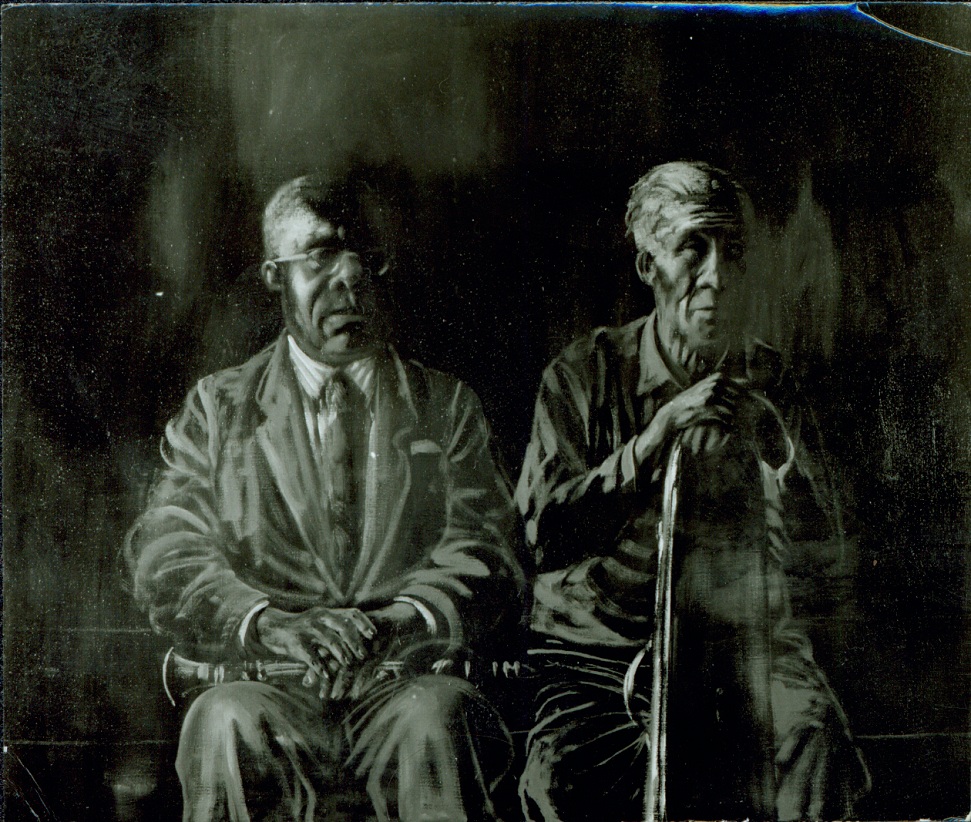

Each night Rockmore invited one of the musicians to come to his studio the following day to sit for an oil portrait. Appointments were for early afternoon to take advantage of the superb north light. These paintings were completed in two or three hours. Most of the musicians sat for Noel as a favor to me but after the series got underway the word got out that it was fun to sit for a Rockmore portrait. At first some were hesitant. One had seen a painting of a musician playing a green trombone; another feared that he would look older than he really was. Some complained that Noel made their skin too dark or their faces too sad. Most of them preferred the pleasant, flattering likenesses produced by street hacks who worked from photographs making pretty but patronizing pictures to sell to tourists. A few would not subject themselves to his brush for fear that he would not flatter them or because they felt they should have a voice in how they should be posed. As the paintings were framed and hung on the walls of Preservation Hall the musicians looked forward to their turn. Within the space of ten months over three hundred polymers and about a hundred oils were completed.

The paintings do more than depict the individuals who shared in this revival. They show the bond between the jazzmen and the link of common experience. Since this series has been completed examples have toured the United States. Their unique merit has helped focus attention on Preservation Hall as a part of New Orleans’ cultural offering.

I find a curious parallel between Rockmore’s jazz paintings and the American Indian paintings of George Catlin. In both instances an artist set out to rescue from oblivion as much as possible the appearance of his subjects. Rockmore, like Catlin, frequently painted several pictures a day. They were not only records of the model’s appearance but also a tribute to the artist’s perception. Often an individual painting in either series thrusts forward with that overpowering quality called “presence” and even those which are less dynamic show the compassion of the creative mind. Both artists worked from life using free, quick, spontaneous layins. The additional detail and development of a painting were confined to the commitment undertaken by the first strokes. Rockmore, like Catlin, is a pure artist of considerable sensitivity.

Those who feel that he subjugated his talent to documentation should realize the sacrifice was justified. The combination of skill and dedication which both he and Catlin exercised resulted in these fantastic collections. It is noteworthy that in each case the artist chose to remain objective and resisted the “cheaply bought” success of painting flattering pictures glamorizing their subjects as folk heroes.

It is easier to appreciate the scope and grandeur of the Catlin project when one sees many of the paintings together. It is similarly true that the total impact of the Rockmore paintings is best felt when viewing a large part of the collection. Visitors drawn to Preservation Hall by the music often unexpectedly discover the presence of the paintings and are profoundly moved.

I find it significant that after Rockmore completed his Preservation Hall series he produced no comparable musicians’ portraits. The isolated paintings of Benny Goodman, Dizzy Gillespie and others are individually valid but they spring from an unmistakably different frame of reference. It is also true that subsequent studies of New Orleans musicians executed from memory or sketches bear a different emphasis.

This series has evoked widespread admiration although occasionally a connoisseur observes that in some instances the personality of the model may have been modified to restate the artist’s mystically profound credo. Rockmore’s major creative contribution is in the realm of fantasy. The scope of his career transcends the Preservation Hall portraits, albeit these have a very special place. The introspective mastery which enabled him to execute these remarkable likenesses is evidenced in all of Rockmore’s works as is his chosen theme - time is running out for everyone.